Human rights: a stop sign, not a road map

Much contemporary discussion of ethics takes the form of claims about human rights. Yet the popularity of this mode of discourse threatens to narrow the range of ethical reflection. Although rights have a limited usefulness as a warning of imminent (or present) danger, by themselves they are a woefully inadequate conceptual resource for structuring reflection and behaviour. Rights provide a negative limit of obligation, borders beyond which one must not pass. But they lack a sense of a positive project, of growing a community, maturing a self in caring and variegated relation to others. The strongest positive statement in the widely cited UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) is that "human beings... are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood." Nearly all the rest of the thirty articles outline protective measures restricting the power of the state over against an individual. This declaration is rightly important, and does serve a very useful function. But it is not and should not be expected to be a comprehensive basis for our life together. And this is not simply because it is a product of its age and culture (notice that we are to live in a spirit of brotherhood, and that - understandably after WWII - the main fear is of state-initiated oppression of individuals); it is because rights themselves are a backstop measure, not the main game.

Much contemporary discussion of ethics takes the form of claims about human rights. Yet the popularity of this mode of discourse threatens to narrow the range of ethical reflection. Although rights have a limited usefulness as a warning of imminent (or present) danger, by themselves they are a woefully inadequate conceptual resource for structuring reflection and behaviour. Rights provide a negative limit of obligation, borders beyond which one must not pass. But they lack a sense of a positive project, of growing a community, maturing a self in caring and variegated relation to others. The strongest positive statement in the widely cited UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) is that "human beings... are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood." Nearly all the rest of the thirty articles outline protective measures restricting the power of the state over against an individual. This declaration is rightly important, and does serve a very useful function. But it is not and should not be expected to be a comprehensive basis for our life together. And this is not simply because it is a product of its age and culture (notice that we are to live in a spirit of brotherhood, and that - understandably after WWII - the main fear is of state-initiated oppression of individuals); it is because rights themselves are a backstop measure, not the main game.

When a relationship has reached a point where both sides are standing on their rights, we are already in damage-control territory. If you have to claim your right to something, the positive goal of the relationship has broken down and it has now become a question of harm-minimisation.

When a relationship has reached a point where both sides are standing on their rights, we are already in damage-control territory. If you have to claim your right to something, the positive goal of the relationship has broken down and it has now become a question of harm-minimisation.

In 1 Corinthians 8-14, Paul argues for the priority of love over rights, of thoughtful passionate concern for the other over the unrestricted exercise of my freedoms. God's love for us in Christ liberates us, not to do whatever we wish, but to do good to others, to serve them for the common good.

Often, our cultural assumption of the good life comes down to each of us pursuing our own agenda as relatively free from outside interference as possible. But there is so much more possible. Others are not obstacles to be negotiated in the fulfillment of my desires; they are opportunities for growth, visible signs pointing to God's coming presence and glory, the primary way in which we love God. The other is a gift to me; indeed, a significant part of that gift is that in the other I too can become a gift.

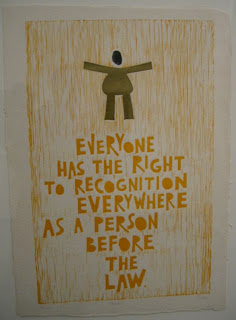

Rights are merely a stop sign; only faithful, hope-filled love gives us a map.

9 comments:

That's a really good way of putting it, Byron. The stop sign picture encapsulates not on the fact that rights can only be a negative limit, but also the fact that are not their own purpose.

Hi Byron,

We've never met but I've been reading your blog for some time and, this morning, felt compelled to let you know that I have found much of what you've written to be wonderfully insightful or deeply moving. This post is a particularly powerful combination of both. Please keep it up!

Nathan.

Nathan - thanks, and welcome to commenting! Where are you from? How did you end up finding my blog?

Jonathan - yes, these were thoughts I had a few years ago, but have been thinking about rights again recently after hearing Joan Lockwood O'Donovan give a seminar on the medieval origins of rights discourse and because we're in the middle of a sermon series on the second half of 1 Corinthians.

Seeing my rights as gifts is a really important step towards acknowledging that I am who I am as a consequence of the relationships in which I exist. I think it actually moves us towards thinking of rights as a debt that I owe others. Of course that idea would never be easy to sell.

Byron I really enjoyed your thoughts on human rights which were as usual well articulated.

I would like to add that not all of the rights in the UN declaration are best viewed as negative limits on obligation - i am thinking in particular about articles 23 - 26 which are better thought of as positive platforms from which much can be achieved. They imply a massive commitment from a society if they are to be fulfilled. Also I think those articles in particular flow from love and concern for others. Anyway I don't want to straw man you Byron as you might be saying this. But i guess what i am thinking is that these rights can be thought of as flowing from love - after all we don't want to straw man humanism either - i hope

Craig - you're right. I didn't mean to caricature or belittle the UN declaration; as I said, I think it is rightly important and serves a very useful function (or a number of functions!). And yes, those later articles do imply a richer social fabric. Thanks for highlighting them. My point was that if we conduct our relationships based on each demanding our rights (even if we base it on the right to be loved and cared for, or on rights that flow out of an understanding of love), then the relationship is already dysfunctional. Rights are a (necessary) minimum standard. Love aims for the maximum.

Hi Byron, I'm from St Albans Anglican church in Lindfield, where Andrew Errington used to attend! It was from his blog that I discovered yours :)

Hi Byron, and Nath!

I agree: this is one of your best posts ever Byron. Near perfect blogging. The pictures are great too; where are they from?

Andrew - thanks. The images are from... well, maybe I should make you guess! But I won't. They are from the UN HQ in NYC. There are a series of artworks illustrating each of the articles of the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights. I wish I'd been able to take pictures of them all, but our tour group was rapidly disappearing around the next corner and so I only got a few.

Post a Comment