The Arctic is melting: 18 reasons to care

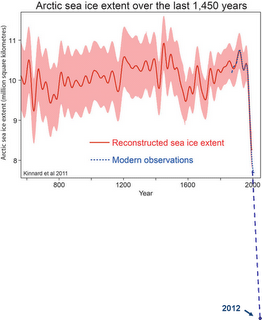

When compared to our best reconstructions of the history of Arctic sea ice over the last 1450 years, the last few decades are, well, unusual. The graph above, which shows the ups and downs of summer sea ice extent over the years gives a sense of just how staggeringly quickly this part of the world is changing. Indeed, the collapse in sea ice is so rapid that it continues to stun even the scientists who have been watching it closely for decades. Back in 2007, the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report said that it was unlikely the Arctic would be seasonally free until after 2100.* Now, the UK Met Office says it is likely sometime between 2040 and 2060, most other Arctic organisations speak about sometime around 2030, while a handful of individual experts warn that, depending on weather conditions, it could be as early as the next Olympics in Rio. There is almost no evidence that this has occurred for at least the last few hundred thousand years (estimates range from 700,000 to 4 million years). *There are different definitions for what "ice-free" means. The most common is when extent drops below one million square kilometres, meaning that there might still be some ice clinging on around the north Greenland coast or in bays and inlets in the high Canadian Arctic, but effectively, the main ocean is free of ice.

Whatever the precise timing, why do we care? So what if some polar bears drown? Why does it matter to me what is happening thousands of miles away in the middle of an ocean amidst a deserted wilderness? Because the Arctic is closer than you think. The effects of declining summer sea ice are many. Here are eighteen reasons to care about the likelihood of a seasonally ice-free Arctic Ocean in the coming years. Only one is polar bears:

1. Polar bears: And walruses, seals and all the other unique Arctic wildlife that depend on sea ice. Seasonal sea ice loss threatens the unique and endemic Arctic biota. The polar bear is an photogenic icon, and as the largest terrestrial predator it instantly commands widespread respect and attention, but there is so much more at stake than simply polar bears.

2. Cultural loss. The loss of sea ice undermines the way of life of various indigenous groups in the Arctic, who rely on hunting and the ice for their livelihood and culture.

3. Infrastructure damage: As the Arctic region is warming, the permafrost that covers the land is both melting and being rapidly eroded. There are many structures and roads built on the permafrost that are already suffering severe damage.

4. Albedo change: Less floating white ice means more exposed dark water, which absorbs more solar radiation, increasing the total incoming heat flux of the planet, and specifically of the Arctic Ocean. The reflectivity of the planet's surface is called its albedo, and the decrease in albedo caused by loss of Arctic ice during the period when it is receiving 24 hours of sunlight is considered by many scientists to be the greatest single threat on this list.

5. Permafrost methane: A warming Arctic Ocean and atmosphere speeds the melt of permafrost in Canada, Siberia and Alaska, not only threatening infrastructure (see #3), but also releasing stored methane (CH4), a highly potent greenhouse gas that degrades into carbon dioxide, making it both a short term climate nasty and a long term headache. The total amount of frozen methane is vast and although it unlikely to all melt quickly, it is soon likely to become a significant and sustained drag on efforts to cut emissions. More emissions from thawing permafrost means less room and time for us to make our own transition away from carbon-intensive energy systems.

6. Submarine methane: Warmer waters increase the rate at which vast submarine deposits of methane clathrates found along the Siberian continental shelf destabilise and are released to the atmosphere, giving a further kick to warming. Some observers are petrified this "clathrate gun" could end basically all life on earth in matter of years through a catastrophic self-perpetuating release. As I've noted previously, scientists are yet to see a convincing geophysical mechanism for this being a sudden and catastrophic release (with consequent spike in global CH4) rather than a progressive leak resulting in an elevation of CH4 with rising CO2. This represents further drain on our carbon budgets, though the precise scale and timing of these emissions are less understood than those from terrestrial thawing.

7. More available heat: To convert ice at 0ºC to water at 0ºC takes energy, even though the temperature has not changed. The considerable energy involved in this phase change is called latent heat. Without ice in the ocean sucking up extra energy during summer, the solar energy that previous went into melting ice can go into the oceans (and later be released to the atmosphere). This is like removing a handbrake, though my back of the envelope attempts to quantify it suggest it will be significantly smaller effect than albedo change (#4). I'd like to see these calculations made by someone who knows what they are doing.

8. Wacky weather: This is something of a wild card and could prove to be the biggest danger to human society. Losing the ice is already changing wind patterns around the Arctic, which in turn affect the weather throughout the northern hemisphere. There is some evidence that more exposed water in the Arctic and a decreased temperature difference between the equator and pole (since the Arctic region is warming much faster than further south) is increasing the amplitude of the meanders in the jet stream. In turn, this slows down progression of the meanders, leading to "blocking patterns", where one region gets "stuck" in a certain weather pattern, whether heatwave, drought or flood. The 2010 Moscow heatwave that killed 11,000 people and sent the price of wheat skyrocketing (in turn helping to spark the Arab Spring), the 2010 Pakistan floods that displaced 20 million people, the 2010/11 record cold winters in Europe and parts of the US and the 2012 US heatwave and drought have all been linked to unusually persistent blocking patterns. Losing the ice may mean we see more of these kinds of things. The jury is still out on this theory, but if not precisely like this, the loss of Arctic sea ice will almost certainly affect wind circulation patterns and so weather both regionally and hemispherically.

9. Greenland melt: Over the long term, this may be the biggest change. The warmer the Arctic Ocean gets, the warmer Greenland is likely to get, and the faster its glaciers slide and melt into the sea. While floating sea ice doesn't affect sea levels (and there's relatively little of it anyway), there's enough ice on top of Greenland to raise sea levels by 7.2 metres (on average). As I read it, glacial draining and calving of the ice sheet is a larger sea level rise contributor than straight melting (thus the recent fracas over dramatic surface melt may not be the key issue for Greenland - remember, this recent melt event cut centimetres off a sheet that averages over two kilometres thick). The real danger is the acceleration of ice flow dynamics (i.e. the ice cube is more likely to slide off the table before it has finished melting). And the largest boost to glacier acceleration is from warming oceans meeting marine terminating glaciers. No one is entirely sure how long this will take, but it is a process that once it is underway in earnest, is likely to have a momentum of its own, meaning that our descendants will be committed to ever rising sea levels for centuries to come. The somewhat good news is that it is also a process that (on present understandings) is assumed to have some physical constraints due to friction (i.e. there are speed limits for glaciers, even in very warm conditions). The West Antarctic ice sheet, being largely grounded on bedrock well below sea level is actually more plausibly in danger of catastrophically sudden break-up, though warming in the Antarctic is currently only a fraction of what is being observed in the Arctic.

10. Resource conflict: An increasingly ice-free Arctic opens up a geopolitical minefield as nations scramble to take advantage of the resources previously locked away under the ice. The starter's gun for this race has well and truly fired, with various oil companies sending rigs to begin drilling for oil and gas this season. As one signal of the seriousness with which this is now taken, meetings of the Arctic council (comprised of nations bordering the Arctic) now attract Hillary Clinton rather than a minor government official.

11. More oil: The presence of significant amounts of oil and gas under the Arctic Ocean has been suspected and known for some time. Less ice means that fossil hydrocarbons that were previously off limits now become economically viable to extract, thus increasing the pool of available carbon reserves and so worsening the challenge of keeping most of them underground.

12. Fishing: Another resource now increasingly able to be exploited due to the loss of seasonal sea ice. Pristine (or somewhat pristine) marine ecosystems are thus exposed to greater exploitation (and noise pollution).

13. Shipping lanes: The fabled North West passage through the remote islands of Canada has been open to commercial shipping without icebreakers only four times in recorded history: 2011, 2010, 2008, 2007. The North East passage has also been open in recent years. These previously inaccessible Arctic shipping routes reduce fuel needs of global shipping by cutting distances (a negative feedback) but also brings more diesel fuel into the Arctic region, leaving black soot on glaciers (a positive feedback). I'm not sure which is the larger effect overall.

14. Toxin release: For various reasons, certain toxins and heavy metals from human pollution seem to accumulate in Arctic sea ice. As it melts, they are being released once more into the environment.

15. Invasive species: Melting ice reconnects marine ecosystems that were previously separated by ice, enabling migration of species into new regions, with unpredictable ecosystem changes as a result. This is already occurring.

16. Ocean circulation? These last three points are more speculative and I'm yet to see studies on them. But loss of sea ice could well change the patterns of ocean currents in the great global conveyor belt known as thermohaline circulation. This drives weather patterns throughout the entire globe.

17. Acidification acceleration? By increasing the open ocean surface area for atmosphere-ocean gas exchange, the rate of ocean acidification could slightly increase. Would this make any difference to ocean capacity to act as CO2 sink or rate of acidification? This could well be irrelevant, but it is a question I have.

18 Political tipping point? The loss of virtually all perennial Arctic sea ice would be a highly visual and difficult to dispute sign of rapid and alarming climate change, representing a potential tipping point in public awareness and concern. If we are waiting for that, however, before we make any serious efforts to slash emissions (especially if it doesn't occur until 2030 or later), we'll already have so much warming committed that we'll pretty much be toast. At best, therefore, this point might consolidate public support for massive rapid emissions reductions already underway. These eighteen reasons can be summarised in five broad headings:

- Direct effects upon local wildlife, human communities and infrastructure (1, 2, 3, 12, 14, 15);

- Positive feedback affects that accelerate the warming process (4, 5, 6, 7, 11);

- Changes to human economic and political systems through the opening up of previous inaccessible resources and routes (10, 13, 18);

- Disruptions to the great atmospheric and oceanic circulation patterns that shape the experience of billions of people directly (8, 16);

- Acceleration of long term threats (9, 17).

UPDATE: My opening graph needs some important further clarification. The unamended graph is a 40 year smoothed average, while the additional material displays year-on-year changes and so is not comparing apples to apples. However, using only 40 year averages to capture the dramatic changes of the last few years is also likely misleading. There is further discussion of this image here, here and here.