Stop the boats! Torture and the agony of being lectured

And we have. Apparently.

Except what we have done is stop (most of) the boats from arriving. Stopped the public from hearing about them. Stopped the xenophobes from having to share our boundless plains with tiny numbers of uninvited people in desperate need.

We have not stopped people getting onto boats, as there are still tens of thousands in our regions who do so, driven largely by genuine and well-grounded fear of life and limb, according to basically every official attempt to quantify such matters. We have probably not stopped people drowning at sea, even if there are now fewer who drown in sight of Australian land. We have not stopped dangerous and possibly illegal things happening on water, we just no longer hear about them from the minister who is meant to be accountable to us for the actions taken in our name. And we have certainly not stopped xenophobia by flattering it with policies designed to woo its votes.

We have facilitated the abuse - physical, sexual, emotional - of thousands, including more than a thousand children, and destroyed the mental and physical health of many. Two have died unnecessarily, one violently, yet no charges have been laid more than twelve months after his murder, witnessed by many (some of whom were then allegedly flogged into recanting their testimony). We have seen abused children used as hostages in parliamentary negotiations. We have violently ended peaceful protests. We have thrown billions at a false solution during a "budget emergency", the annual cost per asylum seeker detained offshore being greater than the PM's (very generous) salary. We have corrupted the governments of multiple poorer neighbours, through leveraging our foreign aid to secure policy outcomes amenable to our purposes, forcing them into impossible Kafkaesque situations so that we might technically have clean hands - and so journalists and human rights commissions can be kept away. We have transgressed the sovereign territory of our neighbour with military vessels on a string of occasions. We have flagrantly breached multiple critical international treaties and undermined international trust and the rule of law. We have dragged Australia's reputation through the mud, behaving in ways whose only parallels are found in dictatorships and repressive regimes.

And yet, for a majority of Australians, these costs are worth it. Because we've stopped the boats. A system of lies, cruelty, abuse, fear and manipulation has been constructed with bipartisan support (at least for the basic policy structure), in order to achieve a goal questionable in value, efficacy and morality. Yet the popularity of the idea that we have thereby reduced deaths at sea makes it all justified.

Let me be clear: fewer deaths at sea is a great thing, all else being equal. But the bottom line is that we simply don't know if our draconian policies have saved a single life. Our government claims to have saved thousands of lives, claims that it's working, but won't show its working.

Let's for a moment assume they are telling the truth. Let's assume that thousands of would-be economic migrants without a genuine fear of death or persecution have been dissuaded from risking perilous journeys on leaky boats run by shonky operators with little regard for their passengers and consequently thousands of those who would otherwise have ended up floating in the Indian Ocean are still safely in their crowded Jakartan apartments without legal protection (or safely incarcerated in Indonesian detention camps). Even then, Tony Abbott's dismissal of the UN report on Australian torture would be irrelevant and misleading.

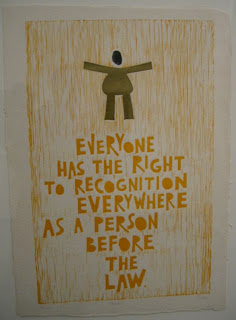

The UN Convention Against Torture does not rule out torture used for bad ends, or torture used by bad people, or torture implemented through particularly cruel mechanisms. It rules out torture. Unconditionally and universally. There are no circumstances under which torture is appropriate. You can fantasise all day about ticking bombs and "noble" uses to save a city from a WMD; such instances would still be torture, and still be banned. You can have inflicted torturous conditions on innocent third parties in order to deter thousands of potential drowning victims from risking a voyage and hence have saved many more lives than you tortured, and still have breached your unconditional, universal commitment never to commit torture. Article 2.2 states: "No exceptional circumstances whatsoever, whether a state of war or a threat or war, internal political instability or any other public emergency, may be invoked as a justification of torture."

The UN Convention Against Torture does not rule out torture used for bad ends, or torture used by bad people, or torture implemented through particularly cruel mechanisms. It rules out torture. Unconditionally and universally. There are no circumstances under which torture is appropriate. You can fantasise all day about ticking bombs and "noble" uses to save a city from a WMD; such instances would still be torture, and still be banned. You can have inflicted torturous conditions on innocent third parties in order to deter thousands of potential drowning victims from risking a voyage and hence have saved many more lives than you tortured, and still have breached your unconditional, universal commitment never to commit torture. Article 2.2 states: "No exceptional circumstances whatsoever, whether a state of war or a threat or war, internal political instability or any other public emergency, may be invoked as a justification of torture."So pointing out, as I have done many times, that stopping the boats has not kept desperate people out of serious danger, only pushed them elsewhere, at one level, misses the point.

Affirming that seeking asylum is a human right and so genuine refugees who happen to arrive on a leaky boat are thus protected by international law from being prosecuted for any irregularity in their mode of immigration, which means that the victims of our torture have been convicted of no crime also misses the point (though I've used this one too).

Even explaining that punishing innocent third parties to deter others from a course of (legally protected) activity is a form of deep moral cowardice still doesn't quite nail it.

It is simply wrong - deeply, wickedly, heinously wrong - to torture people. It is wrong to torture people when you think you are serving a good cause. It is wrong to torture people if you are indeed actually serving a good cause. It is wrong to torture innocent people. It is wrong to torture people who are guilty of every crime in the book. It is wrong to torture as a deterrent to others. It is wrong to torture in secret where deterrence of third parties can never enter into it.

The recent UN report has confirmed in perhaps the most official way possible what has been obvious for some time. The conditions under which we have been (and still are) holding thousands of people are horrendous. The fact that we are holding them indefinitely is brutal and unnecessary. Using mandatory indefinite detention under cruel and abusive conditions as a deterrent to others denies natural justice. Our capacity, even desire, to "legally" commit refoulement stands against every lesson learned about displaced and persecuted peoples through the horrors of genocide and world war. In short: we have become torturers.

So Mr Abbott, what is worse than being lectured to about torturing people?

Torturing people.