On having dirty hands: Clean Up Australia Day

Sermon preached at St Matthew's Anglican, West Pennant Hills

On 1st March 2015, St Matt's held a joint service for all congregations after many parishioners had spent the morning cleaning up local parks and streets as part of Clean Up Australia Day.

Scripture readings: Psalm 104 and Romans 8.18-27.

When I was growing up not far from here, I had zero interest in my parents’ garden. For me, it was too much hard work - tending, watering, weeding - for too little payoff. With the impatience and selfishness of youth, I expected my efforts to result in immediate tangible personal benefits.

But now, I have a garden of my own: citrus trees, a blueberry bush, passionfruit vine, basil, tomatoes, zucchini, silver beet, basil, kale, leeks, capsicum, various herbs (including basil), a compost bin, a couple of worm-farms, some basil and a beehive. I love it! And I'm trying to inculcate an interest and appreciation in my two little kids that I never managed to gain until I was almost 30.

Some things take time to recognise. The patience, attentiveness, humility and willingness to get my hands dirty that I spurned as a youth are now things I cherish and seek to foster in myself, ever mindful of how fragile my grasp on them is.

Soil is now something I have learned to love. The opening chapters of the Bible speak poetically of humans being fashioned out of the soil. Indeed, even the name ‘Adam is a Hebrew pun, being the male form of the female word ‘adamah: soil, dirt, ground. ‘Adam from ‘adamah. The pun even (kind of) words in English: we are humans from the humus, a slightly unusual word for topsoil.* We are creatures of the dirt, relying on dirt for almost every mouthful of food.

*Technically, the dark organic matter in it.

And so I’ve come to love my worm-farms and compost: watching dirt form in front of my eyes. Seeing my food-scraps return again into the nourishing foundation of life from which they came.

But my garden in Paddington is apparently built on a rubbish dump. It seems like every time I dig, I come across broken glass, plastic, old bits of metal. My two year delightedly finds bits of glass and comes running excitedly to show me and I am caught between anxiety that he’s going to cut himself and pride that he is learning to cherish the soil and wants to keep it free of rubbish.

I often find myself wondering: what were they thinking, these people who apparently smashed their bottles into the soil and dumped random bits of plastic? Were they neighbours chucking things over the fence? Was it a former resident who was particularly careless? Was it the result of some long forgotten landscaping that brought in rubbish from elsewhere?

When we moved in, the house hadn’t been lived in for almost 12 months, and the backyard was overgrown. Gradually, as the garden has taken shape, we’ve been cleaning up the mess. And it feels good to be part of setting things right, even if it is in a small, very localised way. This little patch of dirt from which I’ve removed a few dozen bits of glass and plastic, is now cleaner and healthier than it was before.

And I bet some of you have had something of a similar experience this morning: taking a small patch of land and improving it, removing rubbish, cleaning it up, making it a little bit more healthy, more right, less polluted. Maybe you’ve wondered at those who dumped stuff – whether out of carelessness, apathy or haste. Maybe you’ve even got a little angry – it can feel good to be fixing something, and when you don’t know who was responsible for breaking it, it is easy to indulge in a little self-righteous harrumphing.

It also feels good to be working with others, doing something useful as a team, making the local area a little better for everyone. This is an act of service, an act of commitment to a place, an act that affirms that as creatures of the soil, it is right and fitting that we seek to take care of our little patch of it, even trying to clean up the mess that others have made. Both gardening as well as cleaning up the land, are very human acts – they are a kind of work that affirms our connection to the humus.

And when we turn to our passages this morning, we see that they are not just human acts, affirming our creatureliness, they are also, in an important sense, God-like acts. Cleaning things up out of care for others is to be a bit like God.

Our first reading, Psalm 104, is a wonderful poem celebrating the creative and caring concern God has for all of creation. Yahweh, the God of Israel, is here revealed as being the creator and sustainer of all creatures, great and small. God’s care extends not just to humans, but to the great family of life, the community of all creation. Written long before modern ecological science or the development of the concept of biodiversity, nonetheless, this psalm celebrates the diversity and abundance of the more-than-human earth. The psalmist notices the various habitats of animals, both domestic and wild, the times and seasons of their existence, and asserts in faith that Yahweh is the source and provider of all life, feeding and watering birds of the air, beasts of the land and even the monsters of the deep that so fascinated and frightened the inhabitants of the ancient near east.

And the striking thing is, there is no hint here that God’s care is exclusively or even primarily for humans; this psalm does not give us a human-centred view that assumes everything really belongs to us and exists to be used in our projects. No, God cares for humans in their labouring during the day, but the same land is then the abode of wild beasts at night that are also in divine care. God causes grass to grow for the cattle, but God also feeds the wild lions, the wild donkeys, the creeping things innumerable that scuttle under the waves. These animals were not only outside of the human economy, but at least in the case of wild lions, actively a hindrance to it. God’s providential care embraces even creatures that make life more difficult for people.*

*This point, and the language of the community of creation, is indebted to Richard Bauckham's Ecology and the Bible: Rediscovering the Community of Creation. Highly recommended.

Now, within this community of creation we do have a particular human vocation, a weighty responsibility placed upon us to reflect the image of God, to show forth God’s own caring concern for other creatures, to manage and steward the land in such a way that the blessing multiplies and grows. We are indeed invited to be gardeners. But Psalm 104 keeps us from getting too cocky, too ambitious, too self-obsessed in this task. We are to reflect and participate in God’s loving authority, which is always directed to the good of the other. Yet this authority is to be exercised as creatures. We are not demigods, halfway between God and the rest of creation, we don’t float six inches above the ground. We are pedestrian creatures, creatures of the dirt and to dust we will return. Fundamentally, we belong with all the other creatures, under the care of God, and if we are then invited to join in that task of caring protecting, it is precisely as creatures. We care for the soil as those who are deeply dependent upon it.

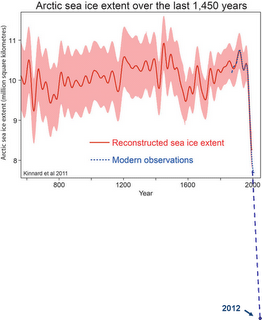

And this is a good reminder to us on Clean Up Australia day. It is so easy, especially in a modern industrial society, to act as though we are above or outside of the rest of life on the planet, rather than intimately connected to it in a vast web of life. Getting our hands dirty today hopefully did some local good, helped make a little part of the world somewhat better. But as we look at our dirty hands, this can also re-ground us as creatures of the soil and we can remember again our dependence upon crops growing, rain falling, soil remaining healthy, biodiversity remaining robust, pollutants being minimised, climate being stable. We have never before in history been so powerful, never before had such amazing technological wonders; but never before have we had such a massive, and largely detrimental, effect upon the habitability of the planet as a whole. There isn’t time this morning to recite the familiar litany of statistics, but they are indeed dire. I’ll just pick one: that as best as we can calculate, the number of wild vertebrates living on the planet has declined by about one third during my lifetime. There are all kinds of factors contributing to this: habitat destruction, hunting, overfishing, climate change, but our stewardship is failing if we are squeezing out these creatures, who are also dear to the one who created us.

And so there is a darker side to today. Our second passage hints at this. In Romans 8, the apostle Paul paints a vivid picture of creation groaning, as though in childbirth, in great pain, in bondage to decay.

If you have the passage in front of you, you’ll notice that there are actually three things groaning. First, there is creation itself, waiting with eager longing, yearning for the day when the current conditions of frustration and decay are no more. Just pause there for a moment and notice the content of Christian hope in Paul’s vision: “the creation itself will be set free from its bondage to decay and will obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God”. The creation itself: this is not a salvation that is purely for humans. We are not to be whisked off a dying planet away to a heavenly realm somewhere else. The creation itself is groaning, yearning, hoping. The creation itself is to participate in God’s great renewal, of which the resurrection of Jesus was the first taste. The Christian hope embraces earth as well as heaven – which ought to be no surprise to those of us who regularly pray for God’s will to be done "on earth as it is in heaven".

If you have the passage in front of you, you’ll notice that there are actually three things groaning. First, there is creation itself, waiting with eager longing, yearning for the day when the current conditions of frustration and decay are no more. Just pause there for a moment and notice the content of Christian hope in Paul’s vision: “the creation itself will be set free from its bondage to decay and will obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God”. The creation itself: this is not a salvation that is purely for humans. We are not to be whisked off a dying planet away to a heavenly realm somewhere else. The creation itself is groaning, yearning, hoping. The creation itself is to participate in God’s great renewal, of which the resurrection of Jesus was the first taste. The Christian hope embraces earth as well as heaven – which ought to be no surprise to those of us who regularly pray for God’s will to be done "on earth as it is in heaven".

The second thing groaning is “we ourselves, who have the first fruits of the Spirit, groan inwardly while we wait for […] the redemption of our bodies”. Again, the Christian hope is bodily – we hope for a bodily resurrection, just like Jesus'. But more than this, groaning is a normal, healthy part of the Christian life. Paul is no triumphalist, who thinks that discipleship consists of ever-greater thrills and bliss. No, we follow a crucified messiah and our fundamental experience is of frustration, which is the necessary precondition for hope, for who hopes for what is already present, already manifest? Groaning is spiritual – not grumbling, mind you – but groaning, a deep yearning desire for all that is wrong to be set to rights. And that deep desire is inspired by God’s Holy Spirit, since it is those who have tasted the first fruits of that Spirit who groan. There is way in which being a Christian ought to lead us to being less content, less satisfied, less ready to make our peace with a broken world as though such brokenness is acceptable.

But if we keep reading our passage, we find that not only is creation groaning, not only are we groaning, but the Spirit also groans. In verse 26, where the Spirit intercedes with sighs too deep for words, it’s the same Greek word Paul used earlier for our groaning: this discontented yearning for the renewal of all things, this deep desire for the resurrection of Jesus to be expanded and applied to all creation, extends into the heart of God. God too groans.

We are again, therefore, invited to be godly. If Psalm 104 helped us to be a little like God in caring for a community of life that extends beyond human projects, Romans 8 teaches us to be a little like God in yearning for the renewal of all things. These two passages give us a way of looking at the world in which the rest of creation is not merely a backdrop to an exclusively human drama. We discover wider horizons as we come to see ourselves as creatures in a community of life, as sharing with all life a fundamental dependence upon God’s provision and interdependence with other creatures. And we are invited to see ourselves as sharing with all creation a fundamental frustration, a desire for our brokenness to be healed, our pollution cleaned up, a desire grounded in God’s own desire that all things be made new in Christ.

Because the pollution degrading our lives isn’t just the rubbish dumped in a local park, it isn't even just the rubbish we’re collectively dumping into the oceans and atmosphere, largely out of sight and not as easily cleaned up with a pair of gloves and some elbow grease, pollution that is altering the very chemistry of the air and water, changing the climate, acidifying the oceans. Even more than these, the pollution degrading our lives is also the rubbish we allow into our hearts when we place ourselves at the centre of our own lives, when we live as though we were something other than creatures in a vast web of life, when we pretend that salvation doesn’t include the rest of creation. All this needs to be cleaned up too.

And so in the context of these passages, our efforts today become far more than just being good citizens, or kind neighbours, or taking pride in our local area, or seeking to make some amends for times we may have trashed the place. In the grace of God, they can become a little taste of the Psalmist’s vision of true creaturehood, a little taste of Paul’s Spirit-filled discontentment with disorder. In God’s hands, our efforts today can become another step on a journey into following Jesus with our whole lives, a journey that may break our fingernails, that may break our hearts, but which is the only path towards true joy.