Baptism: dunk, dip, douse or dribble?

Our daughter was baptised on Sunday morning with little fuss and great joy. Praise God!

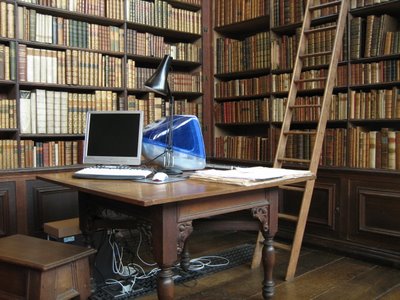

Although the service used a more contemporary liturgical pattern, I took the opportunity to re-read the baptism services in the 1662 Book of Common Prayer. I was struck by a number of things. First, as always, the saturation of Scripture throughout the service. The most obvious difference between traditional and contemporary Anglican liturgical services is not language, but length. And much of what has been cut is the reading of and reference to Scripture. For example, it really adds something to a service of infant baptism to read the passage in Mark 10.13-16 where Jesus tells his disciples (who are acting as overzealous bodyguards) to "let the little children come unto me".

Another more surprising element came in the rubric (the instructions accompanying the words to be said) at the point of baptism. But to show why it was surprising, first a little personal background.

Growing up in a Baptist church, I had only ever witnessed full immersion baptisms (dunking), where the candidate is plunged entirely under the surface of the water and then brought up again (for the hardcore, this can be done thrice: once for the Father, once for the Son, and once for good measure the Holy Spirit). This was how I was baptised just short of my sixteenth birthday. For me, immersion has always made good sense of the apostle Paul's discussion of baptism in Romans 6.3-4, where he speaks of our baptism as our having been "buried with Christ". Thus, full immersion baptism symbolises the burial of the old life and the resurrection to the new life that is experienced when a person is united with Christ by faith.

More recently, and in a tradition that embraces the baptism of infants, I have become familiar with two other methods of baptising: sprinkling (dribble) and pouring (dousing). The former can look to the sacrificial practice in the Old Testament temple (as recorded in the Pentateuch and referenced in the New Testament) and especially to the divine promise of a future cleansing through sprinkling with clean water recorded in Ezekiel 36.25. The latter may look to the frequent New Testament language of the Holy Spirit being poured out upon believers, an event associated with baptism.

As long as it was done in the name of the Father, and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit and using water, all three methods (dunking, dribbling and dousing) were accepted by the early church, though there seems to have been a preference for immersion.

Yet contemporary Anglican practice (insofar as I've seen or heard about it) only ever sprinkles or pours water on infants. Given this, I'd asked our minister to at least splash around as much water as possible, pouring rather than sprinkling. He agreed, saying that the water also symbolises God's love, so the more the merrier.

Therefore, it was with some interest that I noticed that in the 1662 service for "The Ministration of Publick Baptism of Infants" the actual baptising is described like this:

Then the Priest shall take the Child into his hands, and shall say to the Godfathers and Godmothers,Name this Child. And then naming it after them (if they shall certify him that the Child may well endure it) he shall dip it in the Water discreetly and warily, saying,

I baptize thee in the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost. Amen.

But if they certify that the Child is weak, it shall suffice to pour Water upon it, saying the foresaid words,

I baptize thee in the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost. Amen. Notice that pouring is a concession for weak babies; the normal practice is for the child to be dipped. Is this immersion (done discretely and warily)? Or immersion without putting the head under? Is anyone familiar with this practice?

I checked, and the same instruction is found in all the early English Prayer Books (and the Scottish one too). Unfortunately, I was too late to ask for this to be incorporated into the service, but I think it should happen more often. If you are having a child baptised, make sure you take along the BCP and ask your priest for a dipping!