"In my Father's house": some reflections on John 14

However, there was one commonly cited passage I didn't address:

Do not let your hearts be troubled. Trust in God; trust also in me. In my Father's house are many rooms; if it were not so, I would have told you. I am going there to prepare a place for you. And if I go and prepare a place for you, I will come back and take you to be with me that you also may be where I am. You know the way to the place where I am going. - John 14.1-4A heaven-as-destination-of-Christian-hope reading of this passage is probably so familiar that I barely need to sketch it out. Jesus is about to go back to being with his Father in heaven ("my Father's house"), where he is preparing rooms for the disciples (taking almost two millennia and counting to do so) such that one day when he comes back, he will take all believers to be with him. And the way into this heavenly mansion is Jesus himself ("I am the way, the truth and the life", two verses later). Notice, however, that even if this reading correctly identifies "my Father's house" with heaven, this is still not "heaven when you die" - it is heaven at Jesus' return.

N. T. Wright, vocal critic of "heaven when you die" eschatology (and owner of numerous large birds), has suggested a reading of this passage in The Resurrection of the Son of God (2003) that tried to emphasize the rooms (or "dwelling-places") were an image of a "temporary resting-place, a way-station where a traveller would be refreshed during a journey" (p. 446). He pointed out that "my Father's house" is a common way of referring to the Temple (John 2.16-17; cf. Luke 2.49; Matthew 21.13; Mark 2.26). Putting this together with some parallels in Jewish apocalyptic writing that speak of "the chambers where the souls are kept against the day of eventual resurrection", he concludes:

"The 'dwelling-places' of this passage are thus best understood as safe places where those who have died may lodge and rest, like pilgrims in the Temple, not so much in the course of an onward pilgrimage within the life of a disembodied 'heaven', but while awaiting the resurrection which is still to come." (p. 446)Thus, for Wright this passage becomes a reassurance about the intermediate state. God is able to accommodate all those awaiting resurrection. He will not turn any away; those who have died in Christ are not lost.

In his very brief treatment of the same passage in John for Everyone (2004), he seems to have changed his mind. Rather than being about an intermediate state, he now thinks Jesus is referring to our ultimate hope, not going to heaven, but the renewal of all creation to become the dwelling place of God. After again making the point about "my Father's house" as the Temple, he goes on to explain:

"The point about the Temple, within the life of the people of Israel, was that it was the place where heaven and earth met. Now Jesus hints at a new city, a new world, a new 'house'. Heaven and earth will meet again when God renews the whole world. At that time there will be room for everyone." (p. 58)So where does God dwell? Where is his "house"? Although the idea of God dwelling in heaven is a common scriptural image, I think Wright is correct to point to John 2.16-17 as an important earlier reference to God's house. However, even the equation of God's house with the Temple in Jerusalem is problematised in that very passage, which declares that Jesus, in speaking of the Temple, was speaking of his own body (2.19-21). The temple, or house, of God is an image of God's dwelling place. In one sense, God dwells in heaven. In another sense, he dwells in Christ. In a third sense, he will dwell in the new heavens and earth. And yet in John 14 there is a fourth location, a fourth sense of God's dwelling place:

Jesus replied, "Anyone who loves me will obey my teaching. My Father will love them, and we will come to them and make our home with them."

- John 14.23

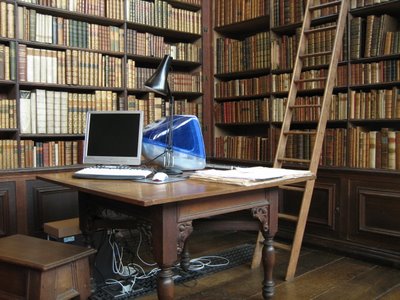

More to come on this...Twenty points for correctly naming the building. Ten for the city. Five for the country. No more than one set of points per person.