The end of the world: replacement or renewal?

At the start of this series, I was asked about 2 Peter 3 (and 1 Corinthians 15.35ff., which I think I've now said something about, even if discussion continues). Here is Peter's wonderful vision of the end:

At the start of this series, I was asked about 2 Peter 3 (and 1 Corinthians 15.35ff., which I think I've now said something about, even if discussion continues). Here is Peter's wonderful vision of the end:

But the day of the Lord will come like a thief, and then the heavens will pass away with a roar, and the heavenly bodies will be burned up and dissolved, and the earth and the works that are done on it will be exposed. Since all these things are thus to be dissolved, what sort of people ought you to be in lives of holiness and godliness, waiting for and hastening the coming of the day of God, because of which the heavens will be set on fire and dissolved, and the heavenly bodies will melt as they burn! But according to his promise we are waiting for new heavens and a new earth in which righteousness dwells. - 2 Peter 3.10-13.

Two initial things to note: first, how positive the final image is - a world in which righteousness dwells, in which justice belongs. Our experiences of justice now remain partial, provisional and imperfectible, but this is a world set to rights. Second, Peter speaks of a new heavens

and a new earth, that is, of a whole

new created order, not simply of 'heaven'.

However, doesn't Peter’s vision differ from my

earlier claims? If 'the heavens and earth that now exist have been stored up for fire' (v.7) and 'the heavens will pass away' and 'the heavenly bodies will be burned up and dissolved' and 'the heavens will be set on fire and dissolved, and the heavenly bodies will melt as they burn' and 'we are waiting for new heavens and a new earth,' doesn't this mean the

end of the world in a 'goodbye earth' kind of way? If the universe gets thrown in the garbage bin, how can we still speak of renewal or liberation? Isn't this

replacement?

Perhaps. Or perhaps not. Peter's language, like that of Revelation, is

apocalyptic in tone. While this term is sometimes used as a synonym for 'catastrophic', it can refer technically to a genre in which major world events are invested with their full theological meaning through using 'earthshattering' language. These dramatic metaphors and pictures emphasise the significance of the events being spoken of, rather than necessarily giving a literal prediction. The second half of Daniel, most of Revelation, and numerous extra-canonical books from around the time of the New Testament give us plenty of examples.

Even if we take these images more straightforwardly, notice that the passage still doesn’t quite claim that the universe will be destroyed. Some translations do say that the earth will be '

burned up' in verse 10, but there is some confusion over this verb* and it is probably better rendered 'exposed' (as above) or '

laid bare'. It is an image of

judgement, rather than destruction; there will be nowhere to hide. The eradication of the heavens is not a prediction that outer space or the earth's atmosphere will kick the bucket while the planet itself survives, but is part of the image of exposure. The 'curtain' of the heavens is ripped back so that the earth and all the works done on it are utterly disclosed to divine judgement. You can run but you can't hide.

*See discussion in comments.

Third, immediately prior to this passage in

2 Peter 3.5-7, Peter uses the deluge (Genesis 6-9) as an pattern of what to expect. Back then, he says, the world 'perished' in the flood (v.6). However we read the flood account, the world was not literally annihilated; it 'perished' in that the old order of things passed away and a new beginning was made.

Thus, I take it that while Peter certainly emphasises the remarkable

discontinuity between now and then (in order to highlight the importance of the future divine

judgement and its implications for our present behaviour - a topic for a future series), the decisive event is nonetheless a renewal and transformation of

this world, not simply its destruction and replacement. Our paradigm: Jesus' own resurrection.

Series: I; II; IIa; III; IV; V; VI; VII; VIII; IX; X; XI; XII; XIII; XIV; XV; XVI.

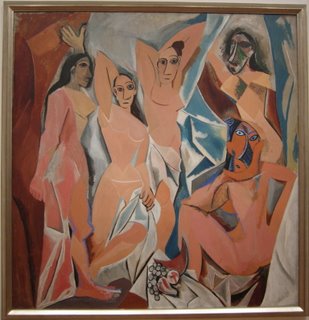

Thanks to Erro for many of the thoughts and references for this post. I'll be very impressed if anyone can pick artist, title or location of this painting. Ten points each.